John Macvicar Anderson (1835-1915) and his second son, Henry Lennox Anderson, were prominent British architects of the late 19th to early 20th C. A substantive portion of their designs was commissioned in the City of London. This body of work is representative of the ‘Classical vernacular’ so prevalent in the Square Mile of that period. Even within that Neoclassical tradition, JM Anderson’s commercial buildings display a particular coherence of applied aesthetic vision. That stylistic consistency and pragmatism are evidence in support of the view (as advocated by Mervyn Macartney, Reginal Blomfield and Banister Fletcher) that so-called Neoclassical and Neo-Baroque architecture should in fact be considered an extension and integral part of a chronologically protracted (indeed still extant) Renaissance movement.

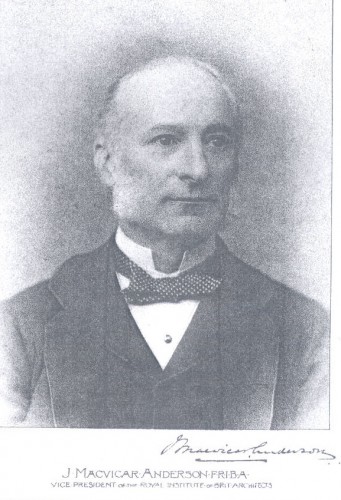

John Macvicar Anderson was the son of Glaswegian merchant John Anderson. After studying at the Collegiate School and the University of Glasgow, in 1851 (age 16) he was apprenticed to William Clarke and George Bell, former pupils of his uncle, the architect William Burn. Soon thereafter, he moved to London to complete his articles directly under Burn’s supervision. The latter proposed him to RIBA, where he was admitted as an associate in 1864. In 1868, Burns took Anderson into partnership and he was elevated to FRIBA in the same year. Upon Burn’s death, in 1870, JM Anderson took over the practice as well as Burn’s house, at 6 Stratton Street.

William Burn’s nearly 60 years of architectural practice focused on churches and country houses and he is considered one of the early practitioners of the ‘Scottish Baronial’ style. This entrée into ‘society’ architecture is reflected in the nature of Anderson’s early commissions, which also concentrated on country houses, but as time progressed his practice evolved to comprise many commercial and institutional buildings.

In the latter part of the 19th C. the practice of calling for entries in architectural competitions became firmly established. John Macvicar Anderson, like Burn before him, disliked the practice and declined all such invitations. As a result, his considerable body of work was all commissioned directly. Anderson became increasingly involved in the running of RIBA, becoming its honorary secretary (1881-89) and later president (1891-94). In these functions he was instrumental in mediating union disputes in the building trade (1891) as well as the sharp confrontation within RIBA between the so-called ‘Memorialists’ and the majority of RIBA’s council, over the issue of registration and examinations of architects. He was also honorary architect for the Royal Scottish Hospital and Royal Caledonian Asylum. In addition to his work in architecture, he was reasonably prominent at the time as a painter, mostly of London cityscapes. In 1915, John Macvicar Anderson died at home.

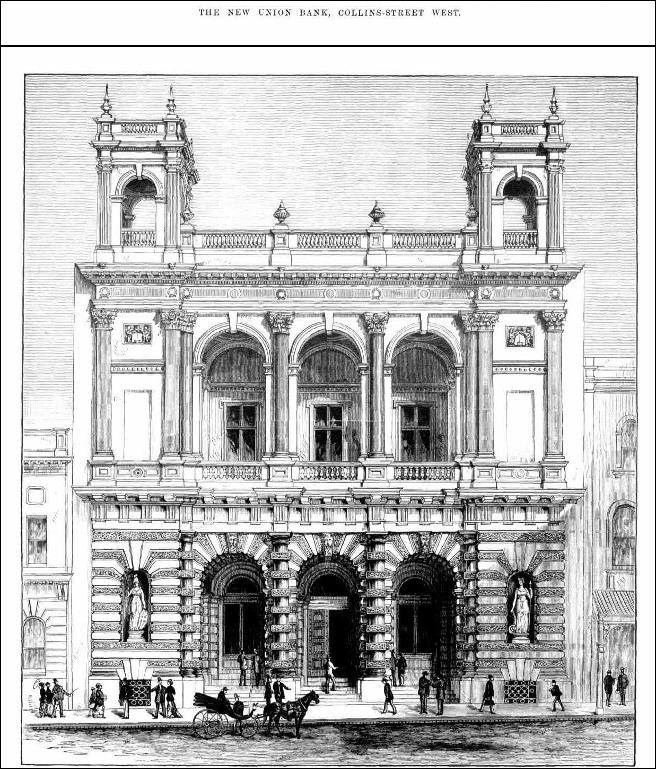

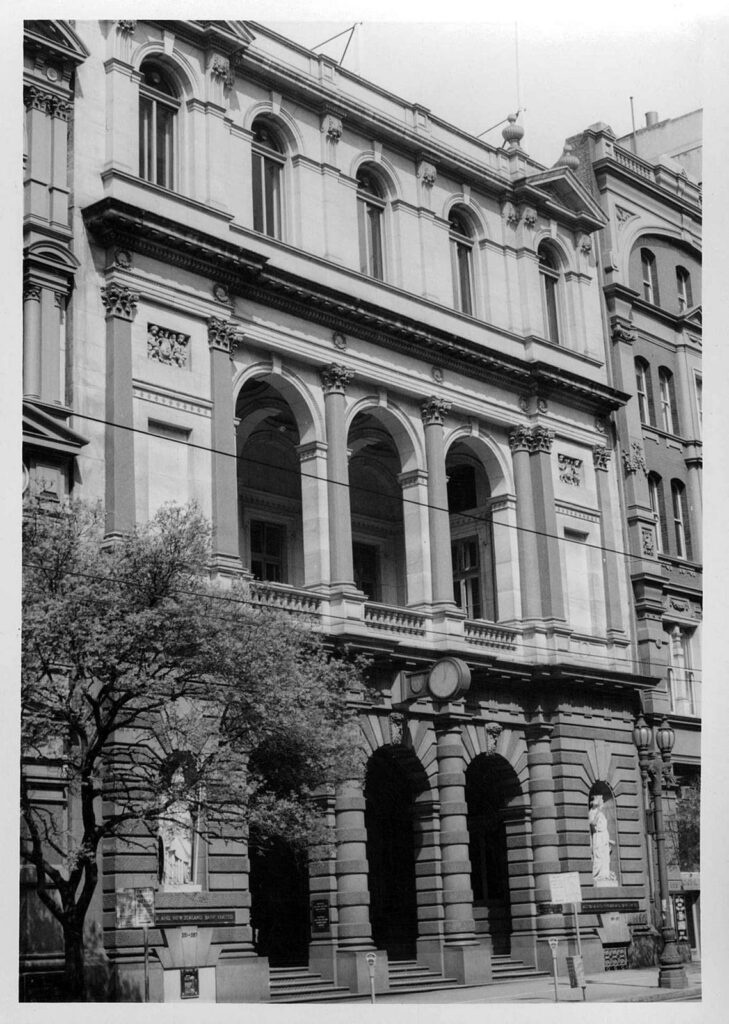

Union Bank of Australia, Melbourne (1878)

By the late 1870s, JM Anderson had accumulated roughly two decades of active practice; mostly in the expansion and renovation of country houses but also encompassing some work in urban typologies such as gentlemen’s clubs and a small private hotel. To date, however, he had yet to design large commercial premises. When the Union Bank of Australia decided to erect a new branch in Melbourne, at 351 Collins Street, it retained Australian architects Smith and Johnson in 1877 for most of the building design. However, the design of the façade was delegated to John Macvicar Anderson.

The dominant aspect along Collins Street consisted of two main storeys, surmounted by a continuous balustrade and accented by square loggia towers at each extremity. The tripartite division between centre and antae, as well as ground storey, piano nobile and terminating elements is clearly delineated.

The raised ground floor featured channelled rustication throughout plus a blocked Doric order in the centre, fronting three tall arched entrances. The slightly projecting antae feature niches, which contained allegorical statues of Britannia and Australia. The following storey repeated the arch motif with a tripartite arcade, this time with a superimposed Corinthian order consisting of engaged columns in the centre and pilasters in antis. The parapet and towers were later replaced by a further storey of five smaller, segmental-headed windows. In antis, these feature an open-base triangular pediment.

The sharp demarcation between ground and subsequent storeys and the formal, dignified use of engaged orders were a recurrent feature of his JM Anderson’s designs for this typology. The Union Bank of Australia building was demolished in the 1960s and replaced by a new stock exchange building. The two statues and the Corinthian capitals were donated to the architecture school of Melbourne University.

Union Discount Company, Cornhill (1889)

Another decade passed before JM Anderson again turned his hand to financial company premises. In the interval, he worked on a number of country house and institutional commission, including the former headquarters of the London Scottish Regiment. The size and siting of the Union Discount Company allowed for a somewhat less varied and distinguished arrangement than the Union Bank of Australia but, here too, late Renaissance and Baroque classical elements were deployed with no reticence whatsoever. Composite arcuated and Doric stylar elements on the raised ground floor are enriched by pediments over the lateral windows. The piano nobile features a Corinthian order, with pedimented windows and balconies. The antae barely project beyond the ashlar of the central section but are further demarcated by the transition from columnar to pilaster uprights. The attic storey is proportionately modest but still richly decorated. Note the use of granite for the columns. The interiors of this building are quite well preserved, by City standards.

Commercial Bank of Scotland, Lombard Street (1890)

From the late 1880s onward, JM Anderson’s rate of commissions for financial clients picked up considerably. 1890 saw construction of his design for the London branch of the Commercial Bank of Scotland. Here, the corner location suggested a canted corner entrance, with the Birchin Lane and Lombard Street aspects built around that diagonal axis. Again, we find the combination of arched voids and superimposed columns. In this case, the Roman Doric is followed by the Ionic order. The corner bay, before a 20th C. upward extension, featured an aediculated window above the attic. The other, surviving aedicule, again above the attic storey, is at the E extremity of the Lombard Street elevation.

Commercial Union Assurance, Cornhill (1895)

The early 1890s were reasonably busy for JM Anderson, whose work in this period included Christie’s auction house, in Mayfair, and the addition of an elegant pedimented porch to the Eagle Insurance offices, on Pall Mall. In 1895 construction began on his largest City commission to date, the Commercial Union Assurance. Rising to five storeys, it reproduced the traditional palette of some of his earlier work. The base, in this case, included both a ground floor (with arched openings and a pedimented aedicule around the central entrance) and mezzanine storey. These two floors were unified by the application of rough bands of rustication. Above them, a giant Corinthian order spanned two central storeys. The uprights were again split between central columns and pilasters in antis. The latter were stepped outward, before returning in the centre. Though more solid than graceful, this building certainly benefited from classical, golden-ratio proportions and the plentiful fenestration. During the digging of foundations for the Lloyds Bank building, next door, part of the building collapsed and it was replaced by a 1929 design by Maurice Webb.

Eagle Insurance and the British Linen Bank, Threadneedle Street (1902)

The year 1902 was a prolific one for JM Anderson, with two separate commissions along Threadneedle Street. Of the two, the original portion of the Eagle Insurance Co. is clearly more modest and, unlike most of Anderson’s City designs, astylar. Nonetheless, we still note the application of tripartite arrangements and careful framing of voids. The effect is gracefully Georgian, both in detail and scale.

Where the Eagle Insurance offices are attractive in their restraint, the British Linen Bank, almost next door, is more frankly declarative, featuring a wealth of detail and subtle surface articulation. Notwithstanding the profuseness of ornament and dignity of proportions, there is a regularity and rhythm that help avoid overly plateresque effects sometimes evident in buildings of this culturally ebullient period.

Coutts Bank, The Strand (1904)

Reminiscent of the Commercial Union Assurance in several details and overall composition, JM Anderson’s headquarters for the private bank Coutts, on the Strand, was later criticised for interrupting a Nash-designed terrace (though it was, itself, replaced by a particularly uninspired glass cage). The base-middle-cap and antae-centre disposition was deployed again. Also repeated were the almost mandatory rustication at the base and (Corinthian) order in the main body. Here the entablature seemed somewhat more academic than at the Commercial Union Insurance, despite both having blank friezes.

Liverpool, London & Globe Insurance, Bank Junction (1905)

If the British Linen Bank is arguably the most calculated of John Macvicar Anderson’s grand financial palazzi, the Liverpool, London & Globe Insurance is probably the most unusual, in plan and articulation. Occupying a sharply triangular plot at the apex of Cornhill and Lombard Street, this building makes the most of its idiosyncratic shape by placing the focus on the corner, which is gracefully rounded and surmounted by a Baroque cupola.

The principal façade along Cornhill is Classically unimpeachable, both in terms of arrangement and the quality of the applied detail. Ignoring the later, two-bay extension at the E extremity, its general shape adheres to Anderson’s typical symmetrical work, barring the barely-present antae. However, the force of the corner elements exercises an irresistible attraction of the eye in that direction. It is worth noting that this is another JM Anderson design that retains some of the fine original interiors.

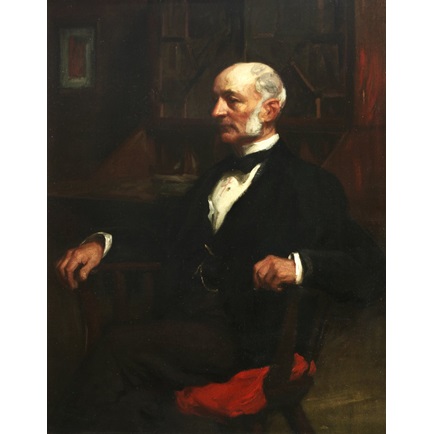

Henry Lennox Anderson was born in 1875 and began to work under his father in 1894. During 1895-96 he also studied at the Architectural Association and he was made a partner in his father’s firm in 1905. He was admitted LRIBA in 1911 and died in 1950, after which the Andersons’ architectural practice came to an end. Though that spans a period of 45 years, it is worth remembering that from 1914 to 1920 and then again from 1939 to the late 1940s (at the earliest) very little was built, not counting the effects of recessions in the interwar years. As a result, the span of institutional or financial industry buildings that we can attributed to HL Anderson is considerably more limited than in his father’s case.

Phoenix Fire Assurance, King William Street (1922)

Although this building was erected several years after JM Anderson’s death, it was co-designed by himself and Henry Lennox Anderson just before the former’s passing. Despite the relatively late date of this work, the composition of the principal façade on King William Street is reassuringly Andersoneque, with clearly delineated antae and a central colonnade. Note that the doubling of the columns and pilasters here occurs both around the central bay (as at the Commercial Union Assurance) and at the internal edge of the antae (as at the British Linen Bank). The blocking and aediculation of the entrance is not unusual though the effect in this case is bolder due to the addition of a large phoenix sculpture in the tympanum. Another intriguing variation, in this case, is the fact that the mezzanine storey, rather than being at one with the rusticated ground floor, is treated as a pedestal for the columns and pilasters of the third and fourth storey, complete with dado and cap.

Guardian Assurance, King William Street (1922)

This is the most prominent project we are aware of, in the City or otherwise, entirely attributable to Henry Lennox Anderson. This large and, for the time, uncommonly tall composition actually consists of two separate buildings, created for the Guardian Assurance (later, Guardian Royal Exchange) and Lloyds Bank. Its prominent position as the terminating vista looking north from the London Bridge approaches is fully exploited here. Furthermore, reflecting the period and, perhaps, the absence of John Macvicar Anderson’s oversight, the Classicism is worn rather lightly, with clear allegiance to the popular stripped Classicism of the interwar years, despite some more academic details.

It is tempting to think, for instance, that the giant Ionic columns would have been interspersed with equally ‘correct’ Ionic pilasters, at an earlier date, instead of the banded piers with no base or capital seen here. Even the proudly Noe-Baroque turret and dome mediate between traditional detailing and the more austere, stripped interpretation of the time.

A substantial and coherent body of work

John Macvicar Anderson was described by architect and fellow RIBA President J. A. Gotch as “…among those elected to the Presidency rather on account of his proved service for the Institute rather than pre-eminence in practice…”. That seems like exceedingly faint praise. Neither of the Andersons proved to be an innovator in the sense of being part of the Whiggish narrative of architecture evolving inexorably towards its Bauhaus-Modernist conclusion. Nonetheless they were both (especially John Macivicar) clearly successful architects that produced some fairly exemplary works within their typology. In particular, the stylistic and aesthetic continuity exhibited by JM and HL Anderson contributed significantly to the Classical streetscape of the City of London and will likely continue to do so. This is doubly notable considering that Anderson refused to participate in competitive tenders and was opposed to advertising.

Partial list of sources

- Buildings of England (London 1, London 6)

- Dictionary of Scottish Architects (1660-1980)

- Directory of British Architects (1834-1914)

- Edwardian Architecture – A Biographical Dictionary

- English Heritage

- Historic England

- Parks & Gardens

Pingback: 37-38 Threadneedle Street, London EC2 – Julia Upton