41 Lothbury and 12 Angel Court, EC2

Built: 1923-32

Architect: Arthur Joseph Davis (1878-1951)

Location: Lothbury

Listing: Grade II* (1977)

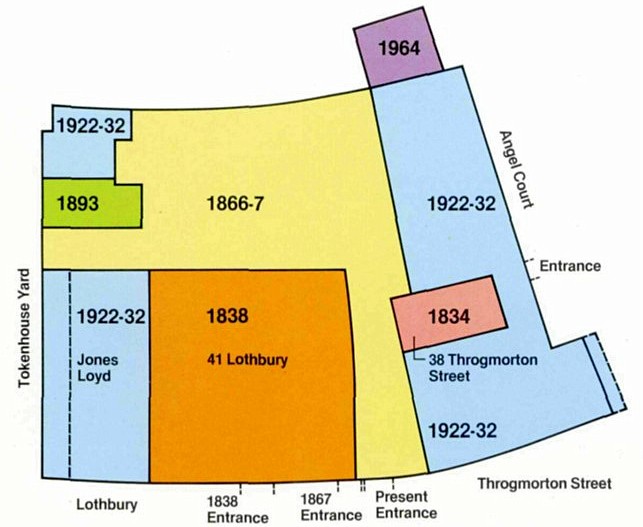

In discussing the companies that commissioned the fine Classical buildings we document on this site, we typically mention the many mergers and name changes that preceded and often followed the construction of any given set of offices. This is certainly true of any component of the NatWest Bank, (see below). Normally, the flurry of consolidations and re-brandings involved in a corporate history that spans close to 200 years would have resulted in numerous changes of registered address. That detail is where the Westminster Bank building at 41 Lothbury differs from the norm, having been a head office for a sequence of related banks from 1838 all the way to the turn of the 21st Century. This is particularly striking considering the presence, between one and three blocks in various directions, of other major buildings associated with NatWest: the 1929 National Provincial Bank offices by Cooper on Princes Street, the Westminster Bank building of 1922, also by Mewès and Davis (largely dedicated to foreign business) on Threadneedle Street, the later NatWest Tower on Old Broad Street, etc.

The London & Westminster Bank was founded in 1833 as the first London-based joint-stock bank (indeed just before Parliament allowed such banks to be established in the City). Its address was 38 Throgmorton Street, on a site currently covered by the building considered in this article. Neither the Bank of England nor the many privately capitalised banks of the City were favourable to it and it was only in 1854 that the London & Westminster was admitted to the Clearing House.

As the bank expanded so did their premises, which took over an existing building at 41 Lothbury from a firm of Army clothiers in 1837. A new set of offices was constructed on the site (1838), with the Portland Stone façade designed by Charles Cockerell while the interior (including a grand banking hall) was designed by William Tite. Further organic expansion and several substantial takeovers followed, with the Lothbury building always retaining its role as head office of the newly created amalgamations. By 1918 it was known as The London County Westminster & Parr’s Bank and was one of the major UK banks. The name was shortened to Westminster Bank in 1923.

Meanwhile, the existing Lothbury property and adjacent ones were gradually demolished and rebuilt in stages, between 1923 and 1932 (some sources state 1921-32), to the current design by Mewès and Davis. The major merger with The National Provincial Bank (1970) did not budge the registered address from 41 Lothbury, as mentioned, and it was only after the RBS takeover of 2000 that the bank, by then known as NatWest, moved its headquarters elsewhere for good.

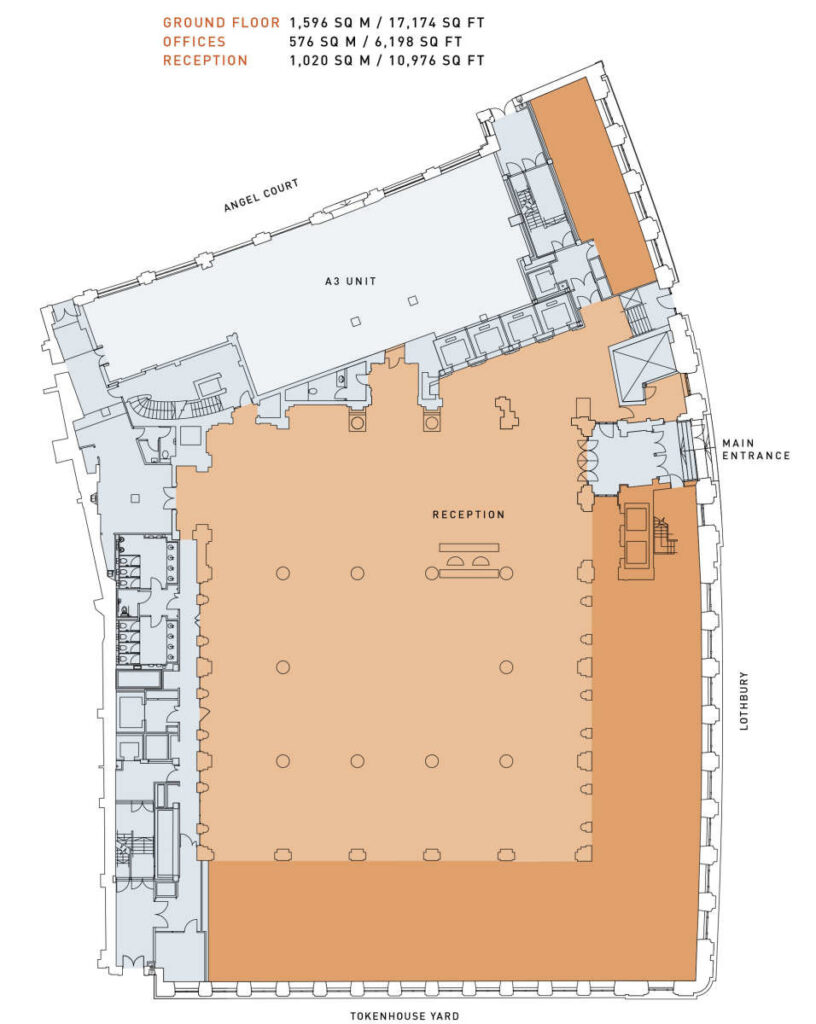

The building at 41 Lothbury consisted of seven stories above ground and three below (containing vaults which were removed in recent years). Notwithstanding the artful concave sweep of the principal aspect along Throgmorton Street and Lothbury, the most unusual element of articulation is the asymmetric arrangement of the façade and plan, with the ‘central’ entrance bays offset to the right (east) and the main banking hall therefore extending to the left (west) of the main foyer.

Externally, this interior arrangement is expressed via the presence of 8 bays to the left of the entrance section and a mere 5 to the right of it. The vertical modulus of both sides is repeated identically. It consists of a windowless base clad in grey granite. The double-height ground storey and mezzanine are gathered behind fluted Ionic pilasters. Above the entablature of that order, there are three storeys, the lower two unified by vertically extended fenestration and a further, balustraded cornice. Beyond that we find two attic storeys, each set back slightly. The detailing of the two lateral expanses is relatively restrained but not neglected. They include a Vitruvian scroll atop the Ionic entablature, ancons on the fourth-storey windows and partly aediculated frames around the attic storeys’ windows.

As dignified and attractive as those elements are, the most striking composition is that of the central section which, despite being off-centre to the building plot, faces squarely down Bartholomew Lane, terminating a vista framed by the Bank of England on the left. Indeed, in another setting, the central portion of 41 Lothbury could be quite a fine building on its own. The base, while still benefiting from the Ionic pilasters, is marked by an unimpeachable triumphal arch composition. The windows at each side of the entrance are more deeply set than elsewhere and the central arch boasts deep coffering, subsidiary Doric piers and richly carved spandrels. The frieze, too, aside from a cartouche that used to bear the bank’s name, sports Renaissance-style bas-relief. The middle portion of the entrance section, tough projecting forward, is quite similar to the rest of the façade except for the more ornate framing of the central window assembly. Quoining is successfully applied to the bottom five storeys. Most spectacularly and successfully, the two topmost storeys, which elsewhere along the façade are recessed attics, here are arranged as trio of baroque arches framed by coupled Corinthian columns with the entablature en ressault. Here, also, the terminating parapet above the top storey carries monumental sculptural groups consisting of idealised ‘seahorses’ at each end and two allegorical figures surrounding a corporate coat of arms in the middle.

Although most of the original internal masonry was removed in the wholesale gutting of the early C21, the listed elements were retained. These include the manager’s office, committee room and, most easily admired, the banking hall. The latter features chessboard marble flooring of green and white marble, a large central glass ceiling that allows natural lighting, a set of 12 giant fluted Ionic columns in the middle and plain Ionic pilasters around the perimeter of the hall. The many apertures are framed by a subsidiary Tuscan order. All of these internal vertical elements are in Subiaco marble.