Davis and Emanuel were an architectural firm that featured prominently in the late Victorian and early Edwardian periods of large-scale transformation of the City of London. In this article, we look at some of their existing work in the City.

Barrow Emanuel (FRIBA) was born in 1842, in the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign, to a prominent Jewish family in Portsmouth. His parents were Emanuel Emanuel and Julia Moss Emanuel. Note that the surname is shown in sources both as ‘Emanuel’ and ‘Emmanuel’ (with two M’s). I will use the single-M spelling, which appears to be more common and was the spelling used by the family, for instance, when erecting a memorial to E. Emanuel.

After a period of pupillage at the Portsmouth Dockyards and the marine engineering firm of Rennie & Sons, Barrow Emanuel attended Trinity College, in Dublin, obtaining an M.A., after which he was chief draftsman at Lewis and Stockwell (shipbuilders and dry-dock owners).

Emanuel’s start in architecture proper came in 1867, when he entered into partnership with Henry David Davis (FRIBA), a co-religionist who had already worked on projects such as the lady Montefiore College in Ramsgate. It is worth noting that Barrow Emanuel’s obituary by the Institute of Civil engineers, states that he played the ‘senior’ role within the partnership.

Not long after the partnership was established, the firm of Davis and Emanuel received a substantial and prominent brief in the form of the West London Synagogue (1870), a Reformed synagogue to which Emanuel belonged (both Davis and Emanuel adhered to the Reformed branch of Judaism). The selection of this firm was not without controversy, with the architect Henry Collins protesting publicly, in letters to The Builder, that the commission had been biased by Davis and Emanuel’s membership in the congregation. This was not the first fight that Collins, who had also submitted a rival proposal, would pick with competing architects and it does not appear to have hurt Davis and Emanuel’s chances.

The West London Synagogue commission was followed by several school projects (including the Grammar School) in Portsmouth as well as the East London Synagogue (1876). The latter had in common with the West London temple that it was a Romanesque-Byzantine inspired synagogue, with the best and most ornate work discreetly reserved for the interiors. The dissimulation of wealth and discretion over grandeur were, at this time, relatively common among the upper echelons of European Jewry.

Having already established a solid reputation, the firm met with further success in winning their second high-profile commission of a ‘Gentile’ nature. This was the City of London School (see below), which held a competition in the late 1870s. Going up against over 50 alternative proposals, Davis and Emanuel won the commission. Despite this success, they did not disdain more workaday projects such as the Lolesworth Building (what we would today call ‘social housing’). Later in the 1880s, Emanuel also met with considerable success in re-developing the side-returns of the Marylebone area road grid (the east-west streets) by building some very charming two-storey houses. Known initially as ‘dwarf houses’ (due to their low rise) and later as ‘bijoux houses’, reflecting their ornamental quality, the first such experiment was by Barrow Emanuel, at 32a Weymouth Street (1886). This project was so successful that several more were constructed, by various architects. Many still stand. After 32a Weymouth Street, Emanuel also designed 33 Weymouth Street and 114a Harley Street (which is actually on Devonshire Street).

Another significant commission around this time was the Meistersinger’s Club, on St. James Street (1886-88). This was followed by Garden House (1889-1890), part of the late-19th C. wholesale redevelopment of Throgmorton Avenue, in the City.

By the late 1890s, Davis and Emanuel began to drift apart and, in December 1898, they officially dissolved their partnership—though Emanuel retained the name of Davis and Emanuel for the business for some time after that. I have no documentary evidence of this, but I am tempted to speculate that the British-sounding surname ‘Davis’ was placed first in the firm title for commercial reasons, as it sounds more British. In 1902, the long-standing employee H. C. Smart was made a partner, replacing Davis.

This very late Victorian to early Edwardian periods marks a particularly prolific one for Barrow Emanuel. The redevelopment of Finsbury Circus led to a commission for the very large and impressive Salisbury House (1899-1901). Emanuel played an even more prominent role in the construction surrounding a new street near Aldgate, Lloyd’s Avenue, working closely with the older and the even more prominent architect Thomas Collcutt. As part of that development, he designed Dixon House, Lloyd’s Avenue House and Coronation House.

Early in 1904, Barrow Emanuel died, aged 62, at the home he had designed for his family at 147 Harley Street (since demolished). Over the course of its existence, Davis & Emanuel had been responsible for architectural work in a great range of typologies including: piers, schools, convalescent homes, private homes, small and large offices, banks, warehouses, flats, country mansions, social housing and, of course, synagogues. Like many accomplished men of this era, Barrow Emanuel was involved in several charities, a member of both professional societies and City livery companies, and a civic leader.

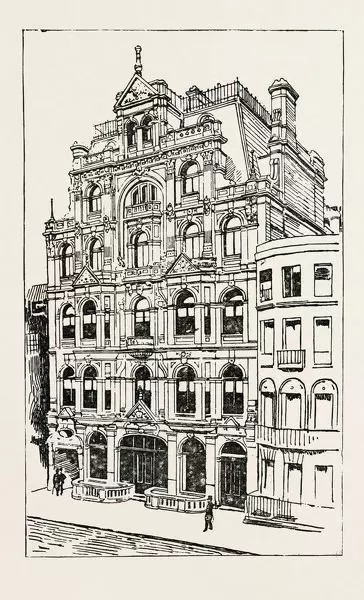

The City of London School (1882)

The City of London School is an unselfconsciously confident building, designed at the height of the Victorian period. As was common for high-end, civic buildings of this time, it reflects several stylistic influences. In this specific case, it also displays a particular richness of composition.

In addition to its innate architectural qualities, the School also benefits from an open, riverside location very unlike the often narrow streets of the City, which shows the substantial articulation at the roof-line to advantage.

According to Buildings of England, the layout and plan of the School was “rather like the compact, multi-storey Board Schools that proliferated in the rest of London from the 1870s”. However, according to the same source, the external appearance was “amazingly unscholastic… [with a] Portland stone facade, rather like a permanent exhibition palace, as if in deliberate contradistinction to the brick Board Schools of the time”. Key differentiating factor include the choice of cladding in Portland stone instead of the more typical brick, sculptural stylistic flourishes (“mainly French renaissance”) and the boldness of composition (those pointy, multiple turrets).

In reality, as unique, even idiosyncratic, as this building appears above the roof parapet, below it the composition is quite well-mannered, while also richly articulated. Unlike some later ornate City palaces, the complexity does not result in confusion. Still, it isn’t every building that can boast a basement with channelled rustication and segmental openings, a main body featuring a projecting Ionic colonnade and- above- a Corinthian arcade, subsidiary columns and aediculation of large, tripartite windows, stylar antae, a central arched entrance beneath a balcony and all that before we even mention the profuse carvings. The sculptural work covers with foliage, escutcheons, statues of prominent men of learning and allegorical figures every inch of the plentiful spandrel space created by the double-depth facade. On top of all that, of course, there’s that roof with those turrets. Although the City of London School was not Barrow Emanuel’s first prominent commission, one might say that from this point on he ‘never looked back’. Many of his designs for City buildings still remain.

Other City of London buildings by Barrow Emanuel

Garden House (1890), part of the Throgmorton Avenue redevelopment of Draper’s Company land, dates to the late 1880s but already displays some of the return to rigorous (though Mannerist) composition that marked a transition from late-Victorian to Edwardian use of the Classical idiom. With 8+1 bays along Throgmorton Avenue and 2+1 along Austin Friars, it includes a channelled ground floor above which projects a slightly cantilevered main body of two storeys with mullioned bays windows and a giant order of Ionic pilasters. A similarly fenestrated attic storey above the cornice follows, as well as a dormered mansard roof. Cladding is mostly Portland stone, with the exception of the granite pedestal along the ground floor. The rounded corner adds some movement to the overall composition but Garden House is a rather much more workaday effort that the City of London School.

During the 1890s, most of Emanuel’s work was outside of the City. Then, in the early days of the 20th C., City commissions began to accelerate.

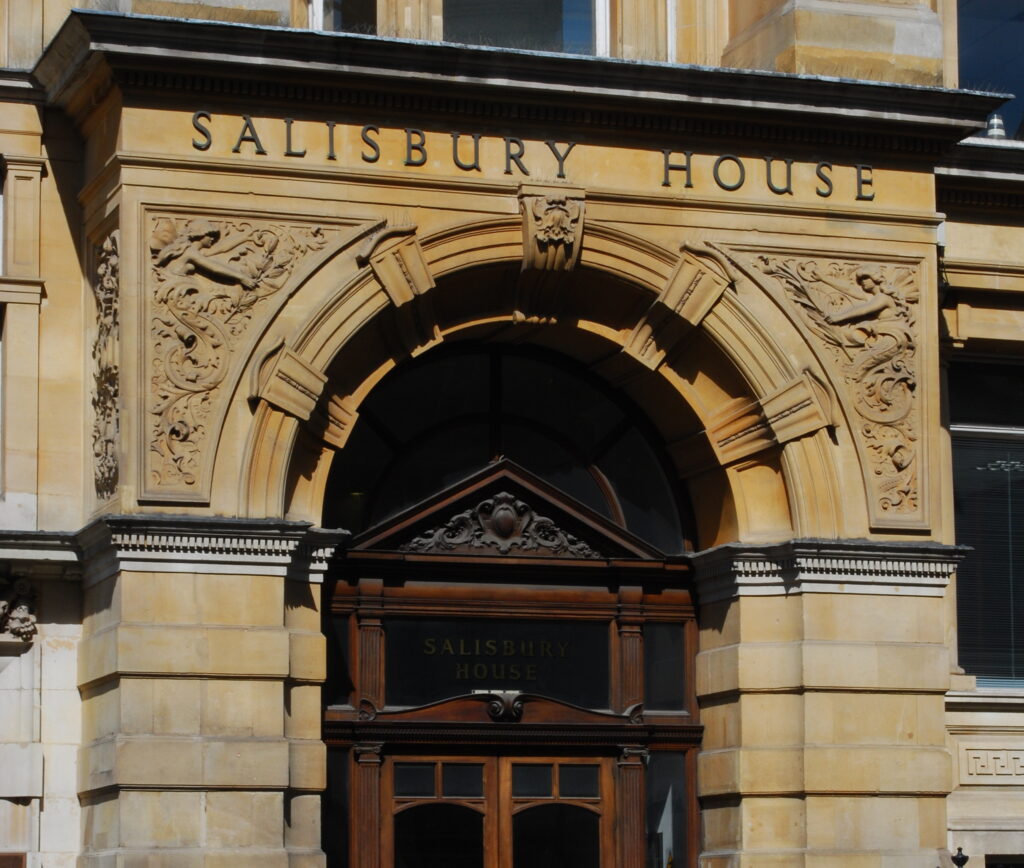

Salisbury House (1901)

If the first thing that strikes one about the City of London School is the daring roofline articulation and depth of surface composition, Salisbury House’s first impression is given by its sheer scale. With over 800 office rooms, it required a large number of large internal light-wells. As Buildings of England notes, this (and other edifices around Finsbury Square) are a very good example of the transition in scale and grandeur from the moderation typical of the mid-late Victorian to the expansiveness of the Edwardian period. This can be said both of the overall size but also the complexity and plasticity of subsidiary elements and applied ornament. Finsbury Circus, which had been laid out at the very start of the 19th C., was completely rebuilt at the beginning of the 20th, after the 99-year leases fell due on what were by then uneconomically small buildings.

Not counting the ‘blind’ western end which abuts Electra House directly, or the light-wells, Salisbury House boasts well over 300 window bays (most of them rather large). It also has six imposing entrances. A full description of its horizontal and vertical organisation would require several paragraphs. Suffice it to say that the long, straight (roughly 90 metres) London Wall aspect is considerably different in organisation from the equally majestic (and taller), concave Finsbury Circus ‘main’ facade.

While certainly replete with detail and enrichment, Salisbury House is not tiresomely over-complex. Despite its monumentality of scale, the wealth of detail and varied treatment across breadth and height effectively create relief of mass.

Another massive building designed by Davis & Emanuel for City clients in this period was Finsbury Pavement House (1890), at the eponymous address, which was replaced by a Brutalist-style building (by Seifert) in the 1970s.

The Lloyd’s Avenue project (1900-1902)

By pre-war standards, Lloyd’s Avenue was a relatively ambitious redevelopment. Replacing some outdated former East India Company warehouses, developer James Dixon and Lloyd’s Register of Shipping decided to invest in the creation of a new road that intersects the eastern end of Fenchurch Street. While Thomas Collcutt won the commission for the sumptuous new headquarters for the Register of Shipping, the other, speculative office buildings along Lloyd’s Avenue were designed mostly by Barrow Emanuel (with some supervision by Collcutt). None of them can equal the prominence of Salisbury House but, taken as a whole, they form a uniquely well-preserved turn-of-the-century streetscape.

The first to be completed, within this set, was Dixon House (1901), at the corner of Fenchurch Street and Lloyd’s Avenue. Arguably, it is the most complex and accomplished among them. Here, as in the City of London School, the composition up to the main cornice is elegantly Classical (and indeed far simpler than the School’s), with the flights of fancy confined to the attic storeys and roofline, in the shape of stacked aedicules and variously shaped gables and pediments. That said, even the more formal lower storeys feature some subtle touches of richesse, such as the subordinate arch elements in the entrances and the combination o engaged columns and-pilasters variations that form the giant columnation.

Over the following year (1902), Emanuel also authored Lloyd’s Avenue House and Coronation House, the facades of which have been retained. Lloyd’s Avenue House is a straightforward design, with five wide bays over four storeys (plus dormers). It is an orderly composition, with an extended, two-storey base featuring banded, shallow pilasters and a rather ornate aedicule with a segmental pediment surrounding the main entrance. The further two storeys are comparatively simple, with thin pilasters and a plain ashlar finish. The symmetry of the façade is emphasised by the referencing of the main doorcase by an enlarged, similarly pedimented dormer in the central bay of the mansard roof.

Conversely, Coronation House, with its honey-coloured Ham stone cladding, is reminiscent in shade of Salisbury House and, although far less grand than that proud edifice, also features a number of imaginatively handled classical devices. These include a cluster of banded columns in a lighter stone near the top of the central portion of the building and several details around and above the main doorway.

The Significance of Davis and Emanuel in retrospect

From the standpoint of narrative evolutionary architectural history, Barrow Emanuel and his partner Davis do not occupy a prominent place. The style of their buildings, certainly those in the City of London, broadly followed the prevailing fashion trends of the day, covering a period just over three decades. It would be difficult to say that the compositional, programmatic or artistic choices they made were in any particular way pathbreaking. There is none of the proto-modernism sought by presentist historians to be found here. What Davis and Emanuel delivered, quite simply, were examples of architecture of their time but with a greater finesse of execution than was the norm. They applied diverse and at times profuse Classical devices with a sense of balance between ebullience and fitness.

Partial list of sources

- Jewish Architects, and Architecture in the 18th and 19th Centuries

- Builder, The

- Building News, The

- Buildings of England (London 1, London 6)

- Dictionary of Scottish Architects (1660-1980)

- Directory of British Architects (1834-1914)

- Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History

- London Gazette, The (27 Dec. 1898)

- Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History, The

- Survey of London