133 Chancery Lane, WC2

Built: 1829-32 (then 1848-50, 1856-57, 1902-04)

Architect: Lewis Vulliamy (then Philip Charles Hardwick, Charles Holden)

Location: Chancery Lane

Listing: Grade II* (1970)

The Law Society of England and Wales was founded in 1823, as the London Law Institution, to establish a professional association for solicitors. By 1825 the “London” part was dropped, as the Society sought to expand its reach nationally and a Royal Charter was obtained in 1832. The building at 133 Chancery Lane, at the heart of legal London, therefore, was planned and indeed built almost at the very start of its existence, with the express purpose of containing a comprehensive legal reference library, as well as housing the Society’s offices. The freehold of the land, however, took 75 years to acquire.

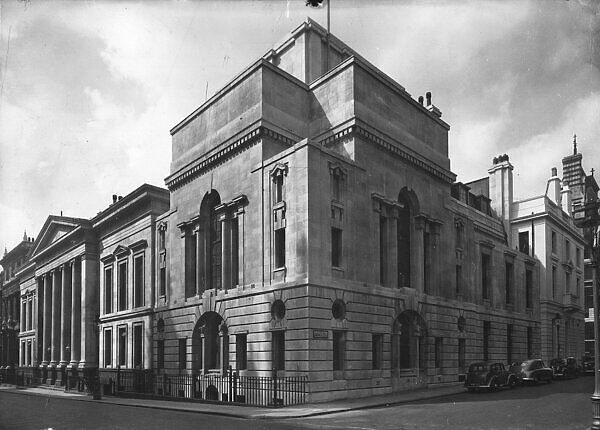

The first edifice (Vulliamy, 1829-32) largely survives, and its main external element is the central pavilion of the Chancery Lane aspect. This is a two-storey, five-bay Portland Stone serenely Neoclassical composition set well back and fronted by a giant, tetrastyle Ionic portico and pediment. The base consists of a crepidoma (set of steps) of Aberdeen granite. To this, two wings were added in the C19. The S one, also by Vulliamy and built in 1848-50, extended by three bays the same arrangement of ashlar, fenestration, basement and restrained entablature established by the original portion. A matching N wing was added in 1856-57 under Hardwick’s supervision, reinstating symmetry. The alignment of these wings, set back from the portico but well forward of the main central body, is an example of well-considered Classical articulation and massing.

In terms of C19 interiors, the best-preserved and most iconic spaces are the Reading Room and Hall (both by Vulliamy). The reading room features parallel Ionic colonnades and cove-vaulted ceiling with a central lantern and galleries. Contrary to the spare exterior, colour is strongly featured not just in the contrasting light blue and gold paint scheme but, especially, the Scagliola marble of the columns. Buildings of England notes that the Ionic order used here and in the front portico is not based on any specific antique example, but rather a general precedent. The Hall was extended to link up with a staircase introduced by Hardwick.

The next major addition to the Law Society headquarters, extending it fully to the corner with Carey Street, was by Holden, at the start of the C20. Although still reliant on a Classical idiom, Holden’s extension makes no attempt to coalesce with the existing fabric, other than retaining the same floor heights and Portland stone cladding. Where Vulliamy’s design is serenely Neoclassical, Holden’s is declaredly mannerist in detail and composition.

The most evident elements of this extension are the vertical modules repeated on both sides of the Chancery Lane – Carey Street corner, featuring a freely interpreted thermal window in the banded ground floor beneath equally heterodox Serliana windows on the second storey. Another idiosyncratic detail is the rather forceful massing created by the extended, blind attic and recessed corner that call to mind an approach to articulation that became more common one or two decades later, at the height of the ‘stripped Classical’ mode.

forefront (corner of Chancery Lane and Carey Street)

Interestingly, the most prominent interior of the Holden extension is the Common Room, which is by far the most Baroque component of this building. Cipollino marble columns (green) and gilding of the Corinthian capitals. The stained glass in the Serlianas is recovered from the Old Sergeants’ Inn and the walls above the wainscoting are richly decorated in a late C19 style between Arts & Crafts and Pre-Raphaelite mouldings by Conrad Dressler. The extensive wood carvings (William Aumonier) add to the dignity and splendour of this room.

A final note about sculptural detail. The C19 portion is almost entirely devoid of carvings, save the coffering in the central section and scrolled brackets supporting the understated canopy of the front entrance. Conversely, the 1902 addition sports allegorical female figures (‘Justice’, Truth’, etc.) by Charles Pibworth atop the mullions of the ground floor windows.