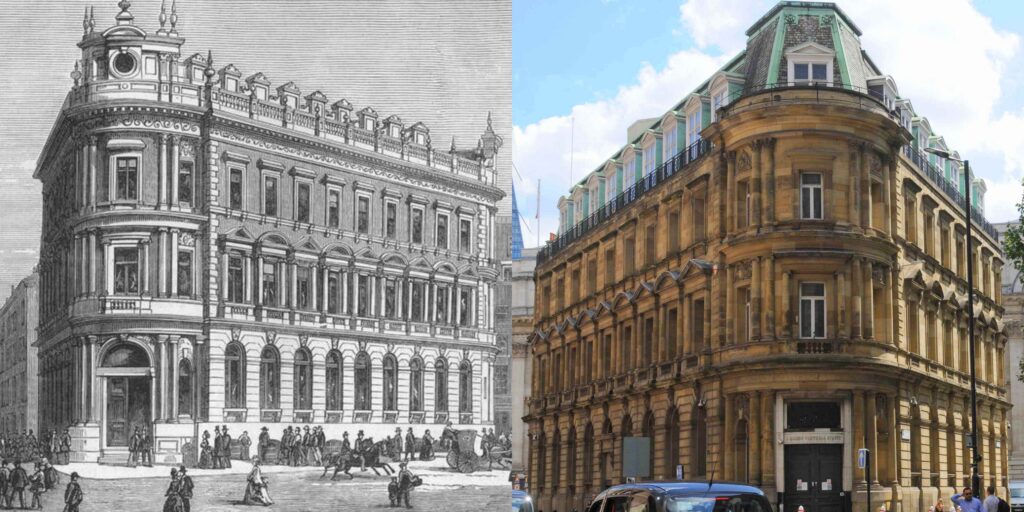

(now City of London Magistrates Court)

1 Queen Victoria Street, EC4

Built: 1873-75

Architect: John Whichcord Jr.

Location: Queen Victoria Street

Listing: Grade II (1977)

The external articulation of this building is roughly that of an isosceles triangle, occupying one of the many wedge-shaped plots along Queen Victoria Street. It rises over three storeys and across seven bays along both Walbrook and Bucklesbury while the longer Queen Victoria Street aspect counts nine bays. At each extremity of that façade, there are two rounded, corner entrances. The single-storey mansard that wraps all around the roofline was added in the 1920s, replacing a prettier, recessed attic storey and set of ornate chimneys.

Despite that intervention, the exterior remains quite classically and rationally organised. The ground floor features channeled rustication and segmental-headed windows sporting agraffe keystones. These alternate an “Old Man Thames” and a female countenance. On the following storey, all windows are fully aediculated, with Ionic columns supporting alternating triangular and segmental pediments. Fronting these, are balconettes with balustraded parapets. The third storey has simpler but still classically framed windows. While the various frontages only feature columns on the piano nobile, the two corner entrance compositions superimpose, “correctly”, a Corinthian order above Ionic columns above Doric ones. The stone exerior is of a darker, warmer colour than the Portland Stone more typically found in the City. Since the 1990s, the building has been repurposed as the City of London’s Magistrates’ Court, formerly housed in the Mansion House, next door.

Although Whichcord designed a substantial number of buildings in the City, the National Safe Deposit Co. and Temple Chambers (at the extreme western end of the City and finished posthumously) are the only remaining survivors of his work there.

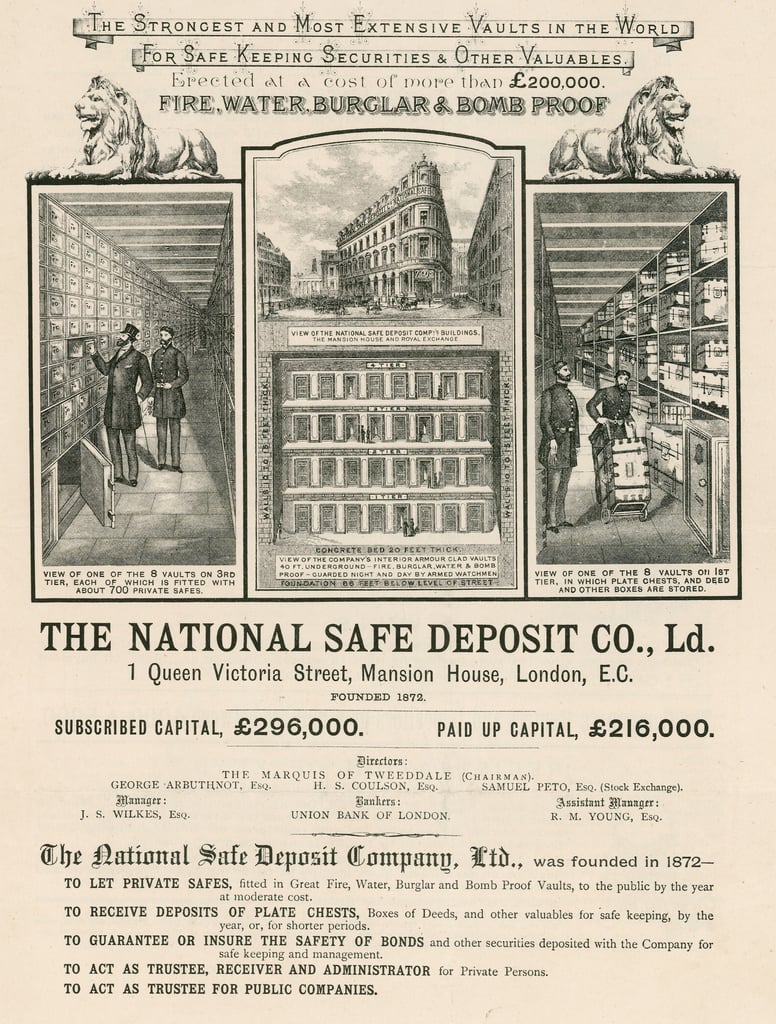

Most commercial offices in the City, however grand their apearance, are comparatively standard buildings, for their time; able to host any number of essentially clerical activities. But for a safe-deposit company, the physical location is a very integral part of the product. The building itself is entirely detatched from other structures (which is unusual in the City). The construction included a 10 foot-thick concrete and hardened brick wall. Past that, there was another brick wall lined with 4½ inch steel plate and iron framing. Within that were the vaults proper, numbering 32 in total. The subterranean portion of the building reached down 76 ft., consisting of a 6 ft.-deep cistern (which would flood attempts at tunnelling), 20 ft. of concrete and the vault rooms themselves. The roof of the vault space was also steel- and iron-clad and the vault doors weighed 5 tons each. It took three separate officers to unlock the vault doors and attempts to circumvent that system would result in the roof reservoir of 55,000 gallons to empty into the vault antechambers flooding them. For more details, refer to articles on “Wonders of World Engineering” and “Archiseek”.

While the national Safe Deposit Co. (which was absorbed by a predecessor to Aviva in 1955) occupied the lower storeys, the upper floors were rented out to other tenants. Principal among them was the Bank of New Zealand, which had offices there from 1889 to 1984; nearly a century!

The flags celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, in 1952.