(now The Ned hotel and clubhouse)

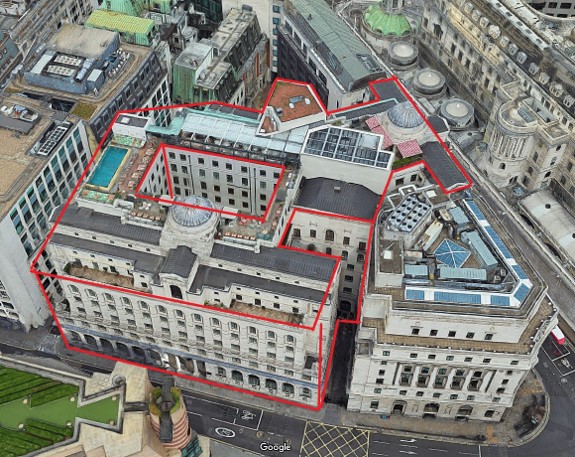

27-35 Poultry and 5 Prince’s Street, EC2

Built: 1924-39

Architect: Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens (1869-1944)

Listing: Grade I (1972)

Considered one of Lutyens’ best formal corporate designs, the headquarters of Midland Bank, like its neighbour, the National provincial Bank, were clearly intended as an expression of commercial confidence, as well s providing modern offices in the heart of the City. These new headquarters combined much larger, open floor plates and steel-framed bulk with historically-based forms and contextual cladding. Both buildings were considered remarkable in their time and examples of a ‘new architecture’. Few bank headquarters of this period attracted a full-length treatment as the Midland Bank headquarters did (A Site in Poultry: The historical background to the Midland Bank Building).

The strong points of this undeniably impressive structure are the legibility and boldly stated subdivision of the lower storeys and the decoratively restrained yet assertive articulation of volume at the corners and upper-storey setback. Ornament is applied sparingly but artfully, including prominent sculptures at the corners of the Poultry façade.

The projecting pedimented attic at the centre of the façade has a wonderful geometric plasticity and is graced with a rich swag relief. The urns that cap its lateral piers also add to the terminal elements. However the overall effect of the central composition is diminished by its appearing rather detached from the solid base, which gives it a sense of aloofness and rigidity.

This effect stems from the treatment of the intermediate storeys (3rd through 5th) which, despite added detailing, seem somewhat wan compared to the lively and unimpeachable lower stories. Some have remarked positively about the presence, here, of a strong implicit order but perhaps more explicit (even if subtle) columnation would have provided a greater sense of punctuation. Altogether, while undeniably successful, the Midland Bank headquarters lack the rhythmic effect of Lutyens’ Britannic House or the daring verticality of his Midland Bank offices at 100 King Street, Manchester.

Another example of the peripheral emphasis of this composition is the bold Doric styling of the lower storeys. Here we see Lutyens’ formal, late-period vocabulary applied with vigour.

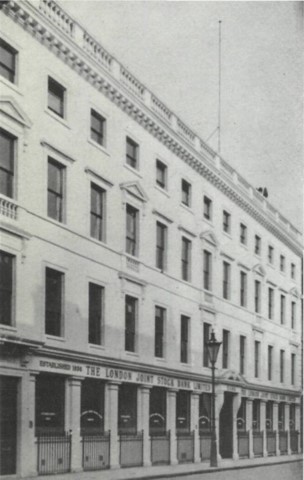

The Birmingham and Midland Bank was founded in 1836, led by Bank of England alumnus C. Geach, at a time when Birmingham was emerging as a major global manufacturing centre. After absorbing many Midlands-based banks, in 1889 it acquired the Central Bank of London and in 1898 the City Bank, gaining full access to the premier global money centre. Another major merger occurred in 1918, with the long-established and internationally-oriented London Joint Stock Bank, then the ninth largest in the UK. This merger made Midland Bank the largest bank in the world by assets and correspondent to 650 foreign banks. The scale of that combination led to government restrictions on further bank mergers which for decades solidified the status of the Big 4 banks (Nationanal Westminster, Lloyds, Barclays and Midland).

The plan of the Midland Bank building is unusual, with two main axes that originate from the Poultry and Princes Street aspects and intersect at an irregular angle. The Prince’s Street portion of the current building was, in fact, occupied by Midland predecessor the London Joint Stock Bank since 1837. The larger portion, facing Poultry, conversely was newly acquired and resulted in the demolition of many smaller buildings.

Lutyens, a very prominent architect by the 1920s, was reportedly a friend of Midland Bank chairman Mackenna and had already done work for the bank (like the Midland Bank building on Piccadilly). The design is from 1924 but, due to economic conditions, construction took place from 1935 (some sources suggest 1930) to 1939. Particular attention was paid to the interiors, which have been well maintained and even improved following the conversion.

Midland Bank was long associated with HSBC and the latter eventually made a bid for Midland Bank in 1992. By 1999 the re-branding was complete and the headquarters were moved to Canary Wharf in 2003. For several years the Midland Bank building stood empty until, in 2012, the founder of the innovative Soho House hospitality empire launched an effort to convert it into a hotel and dining complex.

This transformation is a shining example of re-use, adaptation and conservation. The result, named “The Ned”, after Lutyen’s nickname, is a successful, extremely attractive space that preserves a fantastic building and opens it to the public at a time when vast banking halls have ceased to serve their original programmatic purposes.