57 and 59 Mansell Street, E1

Built: 1719-20 and post-1887

Architect: Unknown (No. 57); Wigg, Oliver & Hudson (No. 59)

Listing: Grade II (1971)

Mansell Street is at the very eastern limit of the City of London, marking the border between Portsoken Ward and the parish of St Mary Whitechapel, in Tower Hamlets. This street is named after a relative of the local landowner, Sir William Leman (his wife’s family, that is). It was laid out in the C17, from Great Ayliff Street (now Alie Street) down to Great Prescott Street (both also named after Leman’s relatives). In 1870, its northern continuation to Aldgate High Street, Somerset Street, was widened and renamed as part of Mansell Street. In 1907, Mansell Street was extended south and southwest, replacing Little Prescott Street and Queen Street in the process.

C18 an even C17 structures survived here well into the C20 but, by the end of that period, Mansell Street was lined with uninspired offices and social housing along most of its length. Thankfully, two period buildings of note survive, at Nos. 57 and 59. Intriguingly, although the two adjoined houses strongly resemble each other, one was built around 1720 (No.57) while the other (No.59) is a much later imitation from the 1880s. This and other historical information in this article is drawn from the very comprehensive entry for these buildings compiled by the Survey of London.

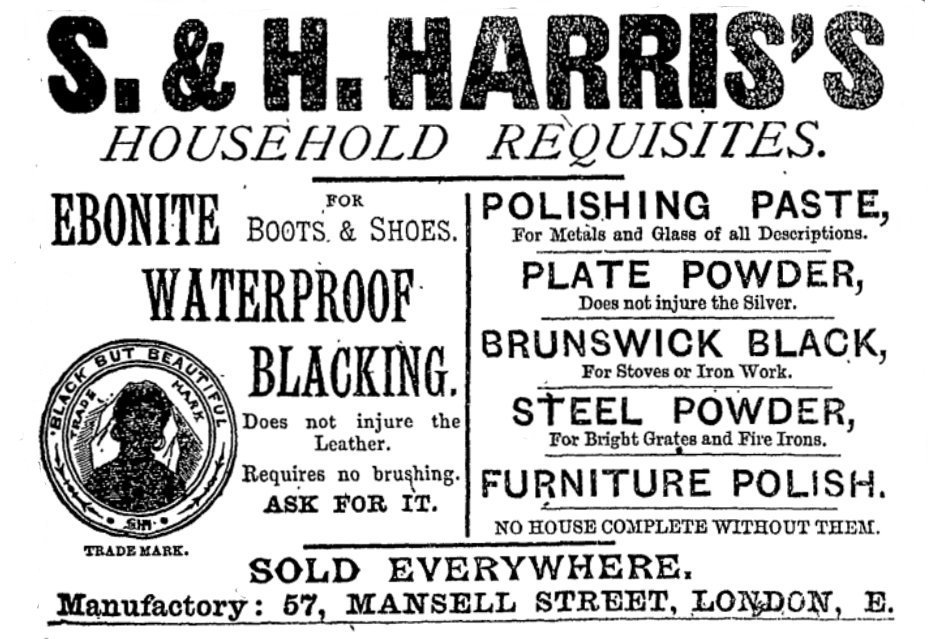

The older structure was erected on the site of existing C17 housing by James Edmundson. Despite being a director of two influential trading corporations, the South Sea Company and the Royal African Company, he was not very rich, working as a purser on HMS Royal Anne. The house then changed hands many times (including ownership by a Sephardic refugee from Portugal, Isaac Dias Fernandes). After several property changes, it was purchased “in the early 1830s by Samuel and Henry Harris, brothers and harness-polish manufacturers.” It was they who, in 1887, tore down two smaller houses and expanded their premises (a mix of housing and business) by roughly reproducing the façade at No. 57 onto No. 59.

Over time, as occurred almost universally in this part of the City and East End, the buildings were put to increasingly commercial use including a string of ‘rag trade’ occupants in the C20. Images from the second half of the C20 show much reduced premises, having fallen prey to indifferent maintenance and unsympathetic alterations. Thankfully, when modern offices were built just north of this location, instead of pulling down the rather tired but historic structures, the developers were persuaded to renovate them. The architectural work was carried out by Trehearne and Norman, Preston and Partners (lead architect: Anthony Millar). In addition to refurbishing the interiors, they also reinstated some ground-storey windows which had been eliminated to create shopfronts, as well as the wall, piers and railing at the front (which are also listed).

Both the Survey of London and Buildings of England have remarked about the application of Baroque details like the doorcase which, at the time of construction in the early C18, would have been somewhat unfashionable; attributing the design to the somewhat archaic tastes of a City merchant. A degree of conservativeness in architectural choices is arguably common in City buildings of the late C19 but whether this applied in the 1720s is perhaps less strongly supported due to limited surviving commentary.

The overall design is pleasingly symmetric, orderly and in a scale that is far from grandiose, given the size of the buildings. The contrast between two colours of brick and the stone dressing is also very well distributed over the façade. Said dressing is applied to the demure string courses between storeys, the open-base broken-pediment of the Doric entrance aedicule, the keystones of the window arches as well as the framing and aprons of the windows in the central bay.