Mansion House Street, EC4

Built: 1739-1753

Architect: George Dance the Elder (1695-1768), George Dance the Younger (1741-1825),

James Bunning (1802-1863), Sidney Perks (1865-1944)

Listing: Grade I (1950)

Architectural description of the exterior

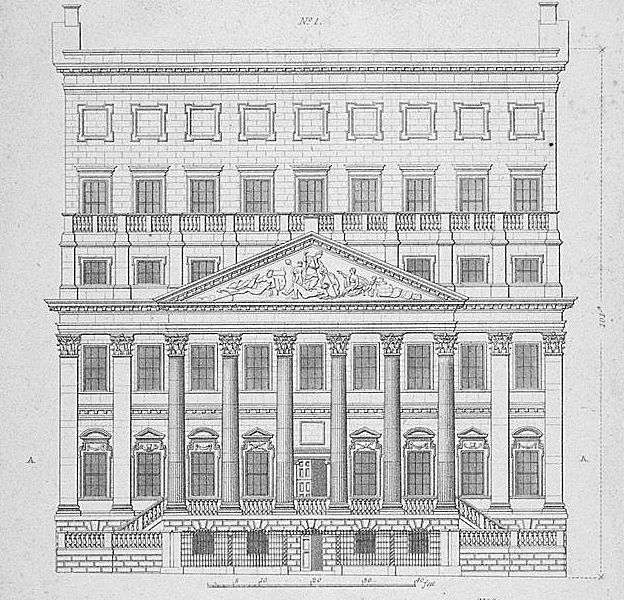

The familiar, principal aspect or façade looks onto Mansion House Street, towards Prince’s Street and with the Bank Junction to its right. It is composed of nine bays framed by 10 shallow, double-storey Corinthian pilasters. Fronting that is the hexastyle fluted Corinthian portico supporting a full triangular pediment. The tympanum contains an allegorical sculptural group showing a personification of the City of London trampling envy and receiving plenty via the Thames (Robert Taylor). The vertical composition begins with a rusticated basement/pedestal with balustraded flights of stairs leading up to the main entrance on the piano nobile. Above the main entablature, there is a restrained but elegant attic storey with balustraded parapet. The removal of the two looming, outsized roof attics (see Characteristics and adaptation, below) clearly added to the dignity and proportionality of the overall articulation.

The side elevations, of which the W one is more easily observed, are rarely considered or shown in the iconography of the Mansion House. Nonetheless they constitute a fine example of Georgian Classicism at the service of specific programmatic requirements. The horizontal composition is markedly tripartite, with 3+6+3 bays. The lateral sections feature a sophisticated composition of doubled Corinthian pilasters (referencing the façade) with the outermost set running flush to the corner and the two inner ones framing a generously fenestrated antae that projects slightly, with a slightly deeper return between each anta and the central section. The latter is astylar, showing the restrained use Renaissance void framing so typical of Georgian architecture.

The subsidiary portico framing the W entrance is part of Dunning’s additional work, adopting a subordinate Doric order. The aforementioned large windows in the lateral sections, of course, provide natural lighting to the ballroom (at the front) and Egyptian Hall (at the back). Note the detail of how the lower windows are of the Ionic Serlian type while the upper, considerably larger ones are simpler, segmental ones, with the coupled pilasters serving a similar compositional effect (of a Roman triumphal arch) as the side lights perform in a Serlian window. It is a skilful and playful use of scale and repetition.

The interior of the Mansion House

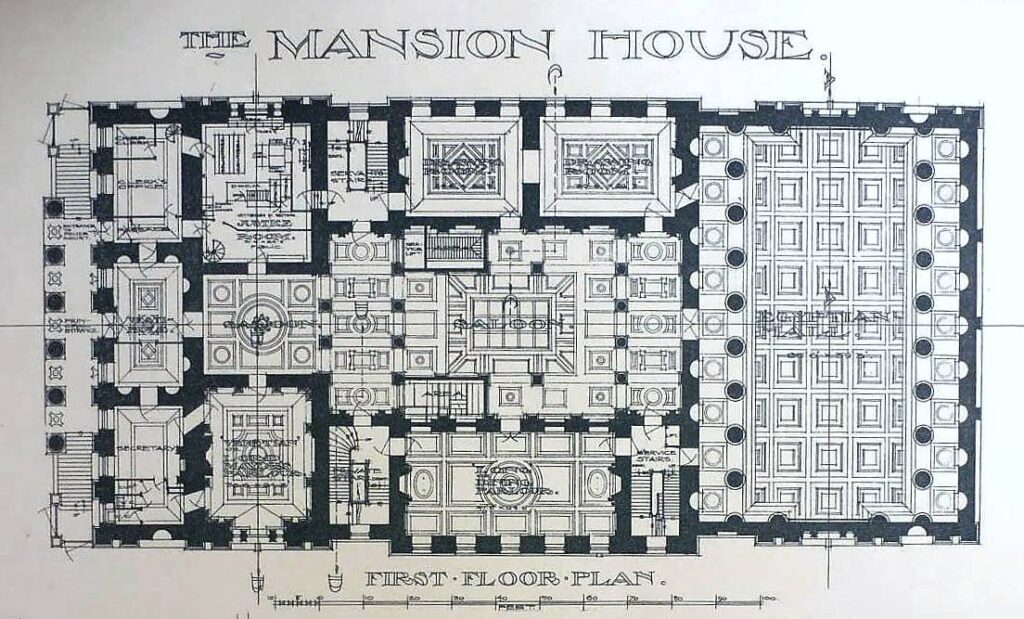

In addition to residential, administrative, executive and judicial functions, the Mansion House was designed to serve and remains an important location for public ceremonies, including highlights such as the annual Mansion House Speech by the Chancellor of the Exchequer. As such, the Mansion House features an unusually large number of formal reception and entertainment spaces.

The most notable, in size and magnificence, are the Salon, the Egyptian Hall and the Ballroom. Smaller spaces like the Drawing Room and Small Dining Room, however, also reflect the pomp and grandeur of City municipal pride.

The Salon (or ‘Saloon’) was created in 1795, when George Dance the Younger covered the central courtyard. The roof was altered in 1861 (Bunning) and again in 1991. While the Doric orders at each end are original to 1795, the colonnades along the sides were introduced in the 19th C.

The Egyptian Hall is the single largest room and occupies most of the southern portion of the piano nobile. Its name derives from a Palladian revival of a Vitruvian design scheme (with no link to Egypt other than Vitruvius’ appellation); its order is a Corinthian one, albeit with round bases in place of square ones.

As part of Dance the Younger’s modifications of 1795, the flat ceiling was replaced by a structurally sounder barrel-domed one, complete with coffering, while removing an existing gallery. The latter was reinstated in 1930 by Perks who also re-opened windows that had been obscured in previous works.

Statuary depicting British literary figures and mythical themes were added in mid-19th C.

The Ballroom, one floor above, is slightly longer (and substantially and narrower) than the Egyptian Hall. The ceiling was modified here, too. In 1842 William Montague re-shaped and lowered it to match the curvature and coffering of the Egyptian Hall. The modestly scaled Ionic order running along the perimeter serves largely to frame the aedicules that, in tune, surround each doorcase. The extended galleries that run along each side are astylar, supported by Rococo brackets interspersed with fine plaster carvings.

Origins and history

The majority of buildings that we cover on this website are commercial typologies from the 19th and early 20th C. – a body of work that is rather neglected by the historiography. The reason we also dedicate some space to better-known civic buildings, such as the livery halls and exchanges, is that the City’s vocation towards Classical devices and composition is strongly linked to the stylistic choices of its institutions, above and before those of individual commissioning companies. Within the corpus of important civic buildings in the City, the Mansion House occupies a particularly relevant place, predating most other civic and commercial buildings (with the obvious exception of the post-1666 churches).

Mayoral residences, offices and ceremonial spaces in the early modern period changed constantly, relying as they did on livery halls and private buildings. A dedicated location for the mayor was discussed as part of the plans for rebuilding the City as early at 1670. However, little was done until York and other major towns in England began to build dedicated mayoral residences.

Up to the Georgian age, City authorities (and its inhabitants) were generally cautious about investing in secular public architecture and it is worth noting that the construction of the Mansion House was in part financed through the underhanded expedient of electing known dissenters to public office in order to levy a fine when the latter refused to be sworn in (which required submitting to Anglican practices).

The site allocated for the Mansion House was an open space which had formerly been occupied in part by the church of St Mary Woolchurch Haw (not to be confused with the nearby St Mary Woolnoth). The former was not rebuilt, after the fire of 1666, and the open space was used as an open market, linked to the existing Stocks Market (sale of meat, fish, etc.). Several small buildings were also demolished to make way for the Mansion House. Like many buildings in this area, the new edifice required deeper, specialised underpinning to counter the fact that it rose over the former streambed of the Walbrook.

Competition for the design brief was keen, involving such well-established architects as James Gibbs, Giacomo Leoni and Isaac Ware, among others. The winner, however, was George Dance (the Elder). He was the son and understudy of a noted City stonemason, Giles Dance, as well as working on projects supervised by his father-in-law, James Gould (surveyor to the South Seas Co.). George Dance was therefore what one might called ‘connected’ in City circles and indeed was appointed Clerk of the City Works in 1734.

In terms of stylistic influences, George Dance the Elder grew up, professionally, when the work of Wren and his immediate successors was still recent or even being completed. Additionally, contemporaries like James Gibbs and the Earl of Burlington, among others, had created a fusion between academic Palladian Classicism and more recent Baroque Continental monumentalism. In other words, the English interpretation of Classicism that is broadly labelled as ‘Georgian’. Those influences are clearly visible in the external arrangement and details of the Mansion House. Much of George Dance’s later work was on churches (like St Botolph Aldgate and St Leonard Shoreditch) but also includes an early version of St Luke’s Hospital (on Old Street) and the first Corn Exchange on Mark Lane.

The Mansion House was a drawn-out project, possibly due in part to its unorthodox financing. It was begun in 1729 and first occupied in 1752, being fully completed in 1753. The brief was for a large building including ample residential areas, offices, a Justice (court) Room, holding cells and several rooms for public ceremonies. Its plan and footprint were restricted by the crowded City setting so that, unlike comparable grand mansions of the period, it included no service wings or mews. The cells, kitchens, storerooms and other service uses were relegated to the ground floor, with the main entrance being placed on the second storey, up a double flight of steps.

Characteristics and adaptation

The most immediately noteworthy elements of Dance’s external composition were: a) the tall, proud hexastyle Corinthian portico, raised on a podium and surmounted by a classical pediment; b) an interior courtyard space, above the ground floor; c) extended lateral frontages; d) more controversially, two tall, pedimented attics running perpendicularly to the main axis of the building. The interior arrangement was also of note. It was characterised by an extensive succession of ceremonial rooms on the 1st-floor, terminating in the large ‘Egyptian Hall’. The 2nd floor, mostly residential in nature, includes a ballroom with an elongated rectangular plan specular to that of the Egyptian Hal. It should be noted that the latter was named after a Palladian speculation based on Vitruvius’ work and has nothing to do with Egypt or Egyptian architecture per se. Staircases occupied each of the four corners of the edifice.

The constraints imposed by its location led to some criticism, with Summerson opining that “it leaves an impression of uneasily constricted bulk … on the whole, the building is a striking reminder that good taste was not a universal attribute in the eighteenth century”. From the start, too, the disproportionate attics were jokingly referred to as the “Mayor’s Nest” and “Noah’s Ark”.

The fact that, with significant but not transformative refurbishment and alteration, the Mansion House has endured far longer than many comparable buildings argues that it was programmatically and perhaps even aesthetically more successful than it is given credit, at times.

A first, significant batch of modifications was undertaken in 1794-95, under the supervision of George Dance the Younger, the Elder’s fifth son. Like his father, he clearly benefited from generations of family activity in the realm of architecture and construction within the City. Unlike his father, he received an extensive formal architectural education, including six years in Rome, at the Accademia di San Luca. He even won a competition organised by the Accademia di Parma. He succeeded his father as Surveyor for the Corporation of London. Among the building he worked on are All Hallows-on-the-Wall, Newgate Prison, St Bartholomew the Less, Bath’s Theatre Royal and many others. Among his pupils were John Soane and Robert Smirke.

In the Mansion House, George Dance the Younger roofed over the formerly open central courtyard, to obtain more usable space. He also removed the rear attic (“Noah’s Ark”) – formerly above the Egyptian Hall – as well as the SE staircase. The main entrance was also modified.

More work was carried out in 1842-43. Including the removal of the front transverse attic (the “Mayor’s Nest”) and the rebuilding of the ballroom to more closely match the proportions and style of the Egyptian Hall. Soon thereafter, in 1846, James Bunning created an entrance, on the W side of the building, to allow the Lord Mayor to come and go without using the busier front entrance.

In 1931, Sidney Perks (who published a book about the Mansion House’s history in 1922) added some discreet attic space on two sides of the central opening and helped renovate the Egyptian Hall and the SW staircase. More modifications were made, especially on the ground floor, by W Insall & Associates in 1991-93, at which time the judicial facilities were moved next door, to the former National Safe Deposit building.

Sources

- Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, Buildings of England – London 1: The City of London, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997

- Sidney Perks, Building the Mansion House – Journal of the Royal society of Arts, London, 1930

- Sally Jeffery, The Mansion House, Chichester: Phillmore & Co, 1993