Between Cornhill and Threadneedle Street, EC3

Built: 1841-1844

Architect: Sir William Tite (1798-1873)

Listing: Grade I (1950)

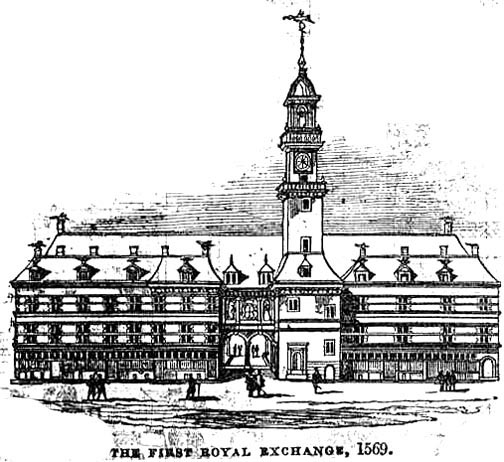

The Royal Exchange was once the pre-eminent institution within the mercantile City of London. It was founded in 1565 by Sir Thomas Gresham on a site donated by the Corporation of the City of London and the Company of Mercers. Both in design and purpose, it emulated the commercial bourses common in Northwest Europe; enclosed markets composed of an arcaded courtyard with offices above it and distinguished by a tall tower. In 1570, Queen Elizabeth I visited Gresham’s Exchange and had it renamed the Royal Exchange in recognition of its commercial importance and to signal her patronage of Gresham.

The original building burned down in the great fire of 1666 and was rebuilt on a similar footprint but in baroque style by 1669. Through the 17th, 18th and early 19th century, it was the location of much trading in physical commodities and financial instruments and as late as the 1820s City merchants would visit it daily. Its large, open courtyard was informally divided into ‘walks’ (by type of trade or provenance of the merchants) and it had a symbiotic relationship with the coffee houses and other private sites where specialized business was conducted. For much of this period, it was the heart of the money market (bills of exchange) and the foreign exchange market.

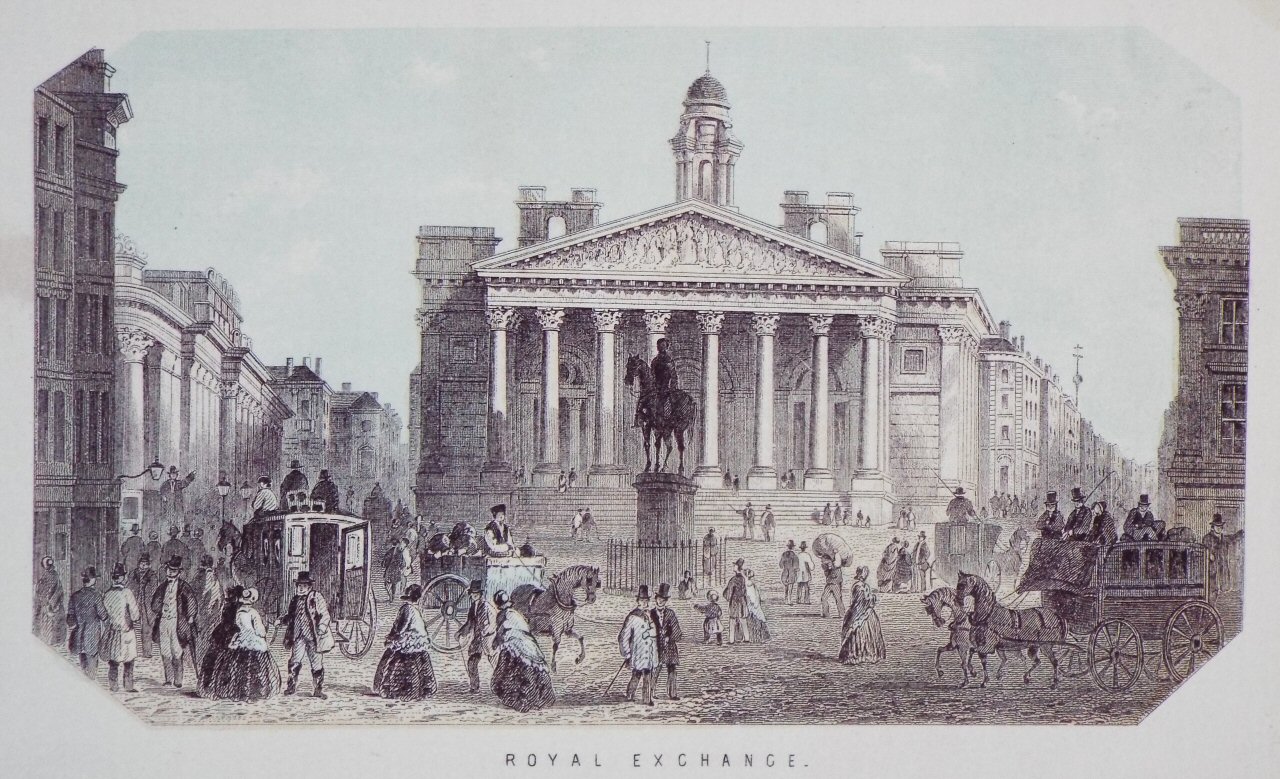

The second building also burned down (1838) and, after some delay, the site was cleared for a third, larger building, less encumbered by surrounding edifices. William Tite, who had been called in to adjudicate the architectural submissions, controversially ended up taking over the project. Queen Victoria opened the current building in 1844. While it retained entrances on Cornhill and Threadneedle Street, the orientation changed from north-south to east-west, with the dominant features being the large classical temple-like frontage on Bank Junction and, at the rear, the tall spire facing east. The plan is trapezoidal. The central courtyard was not roofed over for nearly 40 years after completion but an elaborate, vaulted glass and cast-iron canopy was added in the early 1880s.

By the 1850s-1860s, the Royal Exchange began to decline in importance as specialist exchanges proliferated and improvements in communications began to make inroads against general gatherings of merchants. For many years, it housed Lloyds insurance exchange as well as the Royal Exchange Assurance. Today, it houses luxury retailers and restaurants, with some offices in the upper storeys.

The front of this building from the Bank intersection is so familiar and iconic that it may be worth reminding readers that, although temple-like facades on secular buildings had been around for at least four centuries, this building helped establish the standard look for dozens of banks and stock exchanges across the globe. A prostyle octastyle double portico of tall Corinthian columns carries the entablature and triangular pediment, the tympanum of which contains an allegory of commercial activity that relates it with a rather positivist Victorian idea of religion.

The intercolumniation, between 1 ½ and 2 diameters, is closely spaced, which fits the original ‘institutional’ role of the building. Behind it, the main wall reproduces the entablature and Corinthian order (as pilasters) but also contains arcuated forms in the form of three entrances (the two lateral ones featuring a subsidiary ionic order) and barrel vaulting.

As impressive as the frontal aspect is, much refinement is also found on the sides and rear of this building. The basic composition at each side is very regular. A taller, rusticated, arched ground floor with segmental windows and a mezzanine are vertically united by the giant Corinthian order of pilasters and their entablature. These elements extend around most of the building the theme established by the frontal composition. A balustraded parapet surmounts the lateral perimeter. At the Cornhill and Threadneedle Street entrances, the windows are substituted by entrance gates and greater sculptural ornament and the balustrade is interrupted by capped pedestals surmounted by urn finials, thus adding readability.

The SE and NE corners are gracefully rounded and are recessed from the side walls, with a doubled pilaster effect and a subsidiary centring of the corner composition, which leads nicely to the rear (eastern) aspect. Here, the vertical elements are not pilasters but columns (two attached and two in the round) in correspondence to the east entrance. Surmounting that entryway is a Borromini- and Wren-inspired clock tower with Corinthian columns at the corners supporting the base of a small drum and dome. The grasshopper weather vane (a reference to Gresham) is said to be from the 17th century building.

Following a refurbishment in 1986-1991 by the Fitzroy Robinson Partnership, a further two storeys were added. Because they are set back from the original perimeter line, they are only partly visible from street level. The most prominent feature externally is at the SE and NE corners, where the adoption of a concave articulation above the convex rounded corners produces a historically sensitive and aesthetically pleasing balancing effect of accomplished Baroque style.

The care with which the addition was implemented is more clearly visible from the equally central courtyard, which is open to the public. This majestic space now contains a bar and restaurant. The four interior walls display a renaissance ‘Roman’ module of superimposed orders with returning entablature. The paned glass vault over the courtyard is well executed though, alas, the 1883 one it replaced was indeed finer in its detail.

The ground floor is composed entirely of the masculine rusticated arches and engaged Doric columns. The second storey features an Ionic order including scalloped niches within which aediculated, segmental windows repeat the arch motif. The third storey, part of the 1991 additions, uses Corinthian columns plus window casings that are reminiscent of the external mezzanine ones. It is a very rare and very inspiring present-day exercise in contextuality and refined design.

(credit to Reguiieee, via Wiki Commons)