13 Foster Lane, EC2 (at the corner with Gresham Street)

Built: 1829-1835

Architect: Philip Hardwick (1792-1870)

Listing: Grade I (1950)

From its beginning, the Goldsmiths’ Hall faced Foster Lane, since Gresham Street was not created until after the current building was erected. The history of this building, like that of all livery halls, is closely connected with that of the guild it represents and houses. In the specific case of the goldsmiths, it is a long history indeed. A guild of artisans working in gold and silver is first mentioned in a document in 1180. Hallmarking (certifying metal quality) by royal authority began in 1300 and the Company of Goldsmiths received a royal charter from Edward III in 1327, with Saint Dunstan (who himself had worked on silversmithing) as their patron. Though the Company of Goldsmiths is active in charity work, it also remains heavily involved in the promotion and regulation of its trade. The institute founded by this guild in 1891 was one of the original constituents of the University of London and is now known as Goldsmiths College.

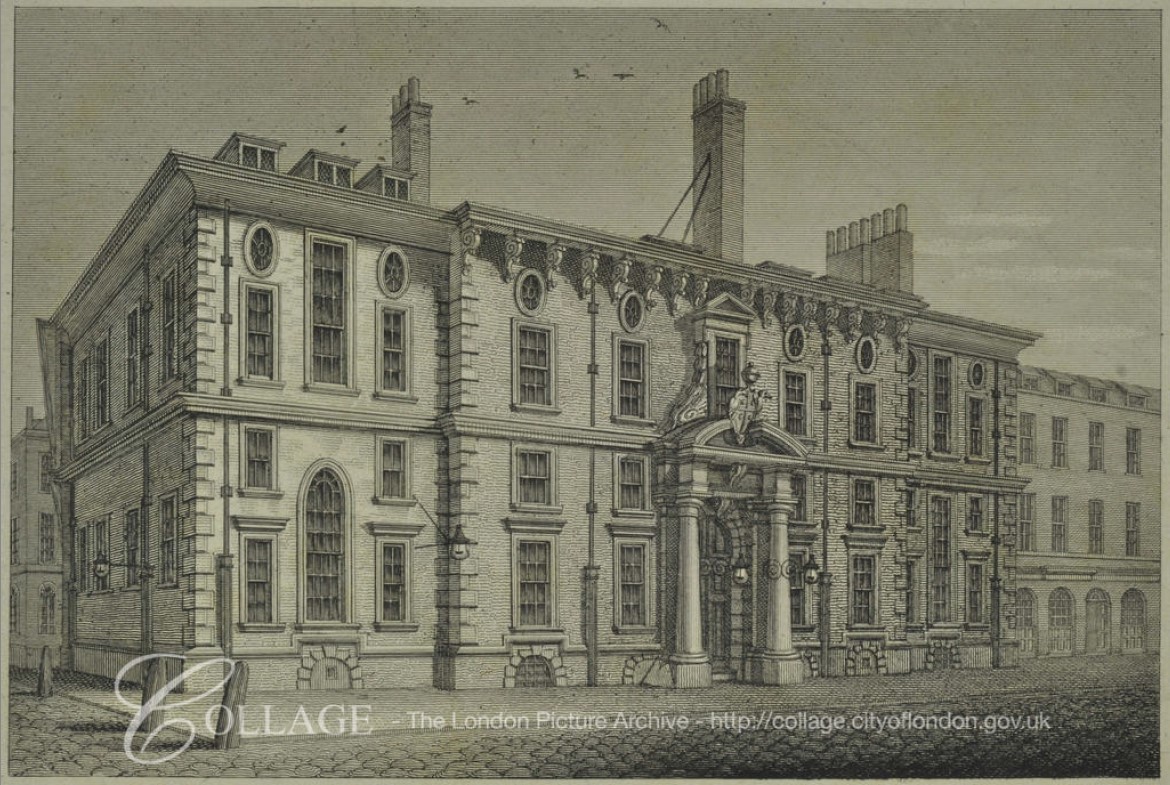

Many goldsmiths had establishments in the area around Cheapside and the first hall, already on the present site, was recorded from 1339, the earliest of any livery company. It eventually expanded to include a chapel, assay house, armoury and granary; all built around a courtyard. The hall was rebuilt by Nicholas Stone in 1635-38, likely with some advice by Inigo Jones. Following the great fire of London, it was rebuilt by Edward Jerman (1669), much along the same lines and this is the hall for which we have the earliest pictorial evidence.

The latest and current incarnation, by Philip Hardwick (with some renovation following WW2 damage) dates from the 1830s and has a Classical Renaissance Palazzo shape with teh addition of later, more Baroque detailing. Indeed, it represents for London a transition from earlier 19th C. Neoclassicism towards a more ornate Classical standard. The facing is largely Portland stone but the plinth is made of Haytor granite. Retaining some of the 17th C. fittings, it was a very grand building, compared to other livery halls of the period and even private clubs. The principal rooms were praised in contemporary accounts: “the rooms are marked by an air palatial grandeur not exceeded by that of any other piece of interior architecture in the metropolis.”

A giant hexastyle engaged Corinthian order defines the central, slightly projecting section of this tripartite facade. The vertical articulation consists of the plinth, channelled ground storey, Piano Nobile and attic storey. The tall Renaissance windows of the Piano Nobile are accented by strongly profiled pediments (alternating between segmental and triangular) supported by consoles. The five windows within the colonnade also feature balustraded balconies.

The intercolumniation of the central bay is a spacious diastyle arrangement (around three column widths between columns) which, together with the slender, unfluted columns and richly detailed Corinthian capitals, give a sense of lightness that belies the lithic solidity of the facade. The plainness of the entablature (with the exception of the modillions and rosettes that enrich the cornice) balances a late-Renaissance, almost Baroque module with Neoclassical restraint. The overall effect is one of refinement. The impression of corporate wealth therefore is conveyed as much via the imposing scale as through ornamental richness.

The exuberantly projecting Corinthian capitals are less elegantly arranged where they top the pilasters at the corner and sides of the building, though the overall effect remains one of great nobility. Note also the central set of sculptural reliefs of arms and trophies by Samuel Nixon. The interiors of the Goldsmiths’ Hall, though partly damaged during WWII, are particularly impressive with the main staircase, the great hall and the court room being the best among them. These are visible to the public on selected open days.